Anthem For No State

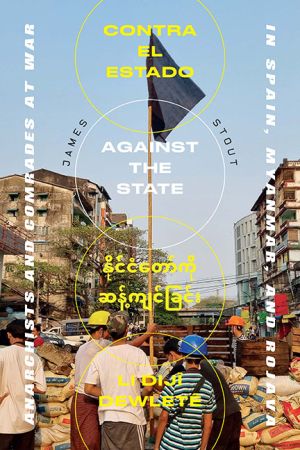

An interview with journalist and historian James Stout about his new book, Against the State: Anarchists and Comrades at War in Spain, Myanmar, and Rojava.

James and I have known each other since 2020. We connected over a shared interest in cycling; the both of us enjoyed wearing lyrcra for hours on end and racing other men in lyrcra on the weekends. He then became one of the first people to help support my early attempts at becoming a journalist when I was just dipping my toes into the profession in 2020/2021. We've met in person a handful of times while covering protests in Southern California. Every time we meetup, we're donning bulletproof vests and helmets. We've been shot at by police with pepper balls and had a skinhead pull a knife at us, all in the same day.

He's written a new book titled Against the State: Anarchists and Comrades at War in Spain, Myanmar, and Rojava, and I had the opportunity to speak with him about it. We talk about hope, armed conflicts, and what we can learn from each revolution in his book.

James is an investigative journalist and historian with a PhD in modern European history. His PhD research was on international antifascism in the Spanish Second Republic and Civil War. He's spent time reporting in conflict zones and along the border in San Diego.

Here's the synopsis:

Young revolutionaries in Myanmar and Rojava, colloquially referred to by journalist James Stout as “anarchists” for their nonhierarchical forms of organization based on mutual aid and solidarity, face incredible danger to pursue their expression of freedom. Against the State seeks to understand these anarchists, to honor their struggles, and ask tough questions about confronting the state. Stout contrasts these contemporary movements with the Spanish Civil War and Revolution where workers in 1936 fought capitalism and fascism. Crucially, the book presents these movements as evolving and innovative, and centers the voices of those too often overlooked in conflict studies and misunderstood by Western radical movements.

It's been edited for clarity and length.

But before we get into it, let me shamelessly promote myself and ask that you become a subscriber today. Good journalism takes work, and your support goes a long way.

How did this book come to be, and what experiences informed your writing?

I was always interested in how the anarchists organized in the time of warfare, because it's not a time that you can sit around and obtain consensus. And anarchists love to have meetings, and there's not always time for meetings. And so I've been interested in that since first reading about the Spanish Civil War when I was 16, 18, whatever, like in high school. And then I was speaking once to this young guy from Burma, Myanmar; either is fine, and this was at this very start of the conflict, and he was talking about his group of rebel fighters, or rebel is not a word that translates well to Burmese, but revolutionary might be better. And he was like, "Oh yeah. Well, when we're planning an attack, we just kind of sit down and talk about it, and if anyone doesn't want to do it, then we won't do it unless we can get everyone to agree to it."

He was kind of talking about what we would call consensus-forming, but he wasn't using that language consciously. And I thought it was super interesting that he had just kind of and his group had arrived, just through mutual respect and a desire to have everyone be of equal value, had arrived at this thing, which was something like consensus on modifying consensus. And I was like, shit, I wonder if this is something that they were doing in Spain that kind of made me want to get off on this kick of why I couldn't find much about the nitty-gritty organizing of it.

In this case, it sounds like they organically arrived at what we understand as anarchist organizing without knowing that's what they're doing.

Yeah, that's what made it so interesting to me, right? Was that, like they didn't have an ideological name for themselves, or they hadn't gone like, I am an anarchist, and therefore I'm organized by consensus. They just gone like, we don't know how to do this, but we feel that everyone should be treated the same because we're all the same. Everything is at stake for all of us. We've given up our lives, and we're risking death, so we don't want anyone to have to do something they're not comfortable with. Given the stakes are so high, how can we organize to maintain that mutual respect? They had arrived at the same place, like they derived it from first principles. It was really affirming, right? That because you often hear like, oh, well, that, you know, this stuff doesn't work under duress, or this works well until you don't have time for a meeting, or what have you. But these guys had done it, like organically, and it seemed to be working for them. And I thought that was really interesting. So it sort of made me think, huh, maybe this is happening more than I think actually. Maybe I have underestimated how you can use this way of organizing, even in really high-stress and high-risk situations.

How do the politics differ in each of these conflicts? Are there defined politics involved in these rebel groups, or did the politics come second?

Going case by case, in Myanmar, the majority of the young people who I know in Myanmar would not have called themselves particularly political the day before the coup happened. Like they were just young people living their lives, trying to get on with whatever they were getting on with, and their political options were relatively constrained within the electoral system. You have the NLD (National League of Democracy), which is not great, to be honest. This is an organization that has been in power during the time when its own armed forces committed a genocide and at the very least failed to stop them. And then you have the military, which is the one doing the genocide, and then you have these different national organizations, but those national organizations are never going to succeed in the electoral system because they're always minorities. So for them, I think it was almost in the absence of having a defined politics for some groups, not all groups. Or some groups developed a more top-down way of organizing. But some groups developed this egalitarian libertarian politics, whatever you want to call it, sort of organically.

In Spain, it came very much like ideology was first, like you had people who were literally card-carrying anarchists. They were members of the anarchist union, and they were often second- or third-generation anarchists. By the 1930s, probably second, but they had not encountered the realities of warfare. Until they did, and then you see this very fierce debate among the anarchists about what is necessary discipline and what is not? What do we have to give up in terms of liberty to gain effectiveness, and what must we not give up? And I found that, like, really interesting, right? They're openly having this discussion, like it's documented, which I write about in the book about their their various feelings on it, especially as the Soviet Union becomes more important in the Spanish Civil War and starts trying to force them to quote, unquote, militarize. To have ranks, to have officers, to do things in a more conventional military way.

And then I guess what you see in Rojava is something of a mix of the two, because you have this, there's an ideology, and it's very strong. And people are extremely committed to it, but it evolves over time. It goes from being a sort of Marxist and Leninist independent, sort of, we will have an independent socialist state for the Kurds, an independent communist state for the Kurds, whatever, to where they are at now. Political thought changed, and the movement moved with them, as did their organizing. The way that they do things now is derived from a number of sources, and they'll be explicit in saying that this wasn't how they did things and that they've changed, and I'm sure they will continue to change. They'll use the word paradigm a lot, and I'll talk about moving beyond the paradigm of the state and into these different paradigms that they use right now. So like for them, as they changed their way of seeing things ideologically, they also changed their way of doing things.

What is the state generally, and in these contexts, how did they end up in opposition to the state? What do they want in its place?

We define the state as an entity that has a monopoly on legitimate violence and it can enforce its rules through the use of violence. That is a fundamental disagreement that they all have with the state. It is this entity that can inflict violence upon them to which they have not consented.

If you want to understand what a state is, here's a good place to start.

Then in Myanmar, that's because the military stole the election and/or just did a coup. In Spain, it's because the military did a coup. And in Rojava, it's because there isn't a state, as the Syrian Arab Republic crumbled because it was illegitimate. Assad kind of legendarily rigged elections to an almost comical degree. And so they had not consented to that, and the state had actively tried to erase Kurdish people through its Arab Belt programs. And so for them, there's a rejection of two states: the Syrian Arab Republic, and then what they were called Daesh, the Islamic State of Iraq, and Bilad al-Sham that also imposed itself on people without their consent.

So at the core of their objections is this idea that people shouldn't be held accountable to rules with which they did not consent and which they are forced to comply through violence, and I think in terms of what they want, it varies hugely.

Like the idea of federalism in both Syria and Myanmar is thrown around a lot. But that can mean a lot of different things. It can mean that communities govern themselves and are responsible for deciding which rules they are held accountable to and how that accountability happens. Or it can mean something more, like a US system. And I think that depends on who you're speaking to and probably when you're speaking to them because, as we can see in Syria right now, there is a state that can enforce its will on people through violence. They did it two weeks in Aleppo, and it's a different state to the Assad state, but still a state, and it's still doing, I mean, they were launching rockets into civilian neighborhoods. It's a sad shit.

But then, on the other hand, like the DAANES, while it's not a state, sometimes does state things. They prohibited people from celebrating the success of the Syrian revolution in December. I'm not aware of them like arresting anybody or compelling anybody to comply with that through violence. So that's distinct, but still like prohibiting people from doing that. It's not great, like it's not, you know, 10s of 1000s of people died in Syria to be free, and they should be able to celebrate what they want and say what they want. So in that sense, it's something like state behavior.

And as I said in the book, we can disagree with actions that any of these groups take and give them criticism on the basis that all of us want something similar. Like human liberation, not being forced to do things with which you don't consent through violence is our goal. We can and should, therefore, give criticism, as I try to do sometimes in the book.

I think what each of them wants is distinct, and even within each of the movements...but within each of them, there are really distinct end points for what they want. But they all share this objection to being compelled through violence to do things which they didn't consent to do.

In all of these situations we're talking about armed resistance, and there's a degree of, a flavor of, anarchism and leftism in our country here that fantasizes about it. Why is violence necessary by the people in overthrowing the state, and what are the realities of that violence on the ground?

I think all of these people had tried to make their claims peaceably. If you look at Spain, you see the anarchist kind of going into the Republic being like, how do we deal with this? Is there a way that we can get what we want and find an accommodation with this? And you see things like anarcho-syndicalism, like through control of unions, thinking they can move towards a more liberated society that way.

In Myanmar, you saw people really, really like, follow nonviolence all the way down the path to the point where it was untenable. You saw people standing in the streets with funny signs, with signs asking the world to help. With demands that they wanted to make of the government, and the government just killed them in massive numbers. And at some point, those people realize that the only way I'm still going to have a voice is if we defend our right to have one. It doesn't matter if we're winning the argument because we're losing the fight, and we won't be here to win the argument. I've heard this like this trajectory outlined by countless young people from Myanmar, who I've spoken to right that they didn't ever see themselves as sort of people who would take up arms against the government, but they were backed into a corner, and they had seen generation after generation try to protest and end up dead in the streets, and they tried to protest, and they saw their friends in the dead in the street, and at some point they just said we're not doing this again. We're going to do something different. And what they decided to do there was to take up arms. And the path towards a use of political violence is a dangerous one.

I hope at no point in the book I'm glorifying the violence that is part of many people's liberation struggle, like the people who I'm writing about in the book. They would rather it wasn't, and I would rather it wasn't. And I think people in this country have a particular sort of fetishization of violence. Sometimes I see this on the left because it's something that they've only ever seen on a screen and like it. It's something that, in reality, is horrible. Throughout the writing of this book, I have seen so many wonderful people, so many bright, young, principled people's lives ended because that is the nature of war. Good people die. It's not like the main character dies. It's not like a movie in that sense. And I think all of them are very aware, I have met so many people who are so young and already so scarred by conflict, physically and emotionally, that none of them would want this for anyone, and I don't think we should want this for anyone.

But I think that there are things that we can learn that we can use in situations that are much less dangerous, right? Like if people can deal with interpersonal and interorganizational disagreements with differences ideologically in that high-stress situation, then maybe we can learn something, and we can deal with them in our everyday organizing or everyday lives. And so I wanted to kind of try to take that from the book.

I think about what they're up against and how they've been able to, sort of like, have any sense of wins because it's the David versus Goliath thing. What are they up against, and how are they overcoming the military power of the state?

It's an overwhelming force. I've spoken to people in Myanmar who, when they took up arms, the arms that they took up were BB guns that they made with, like lighter gas they had, like a butane lighter gas canister, and the gun, like concentrated that gas somehow, and then you lit it, and that caused a small explosion, and that propels A BB out the front. Or slingshots, or like muskets that would have been outdated at the turn of the 20th century, or like .22 rifles that are great for hunting squirrels but entirely inadequate for this kind of thing.

The disparity in force was overwhelming, but they had things that the government didn't have, right? They had the support of the people. In some cases, they had the technology that the government didn't have, like with 3D printing a gun. Specifically, the government couldn't really fathom that when they first started capturing these 3D-printed guns, they'd be like, huh, it's a tiny shock. They couldn't work out what it was. I think at first they probably thought they were like water pistols or something, but over time, they obviously realized what they were.

What keeps them going is the support of people. And those people are all around the world, like those 3D-printed guns that they used in Myanmar weren't designed in Myanmar. They weren't designed by Burmese people. They were designed by an American guy and a Kurdish guy living in Germany. And like those people who designed them had no idea what was going to happen in Myanmar, and one of them was dead by the time that we realized that they were being used in Myanmar. However, I was fortunate to interview the other guy who designed them. 3D-printed guns can be something of a difficult topic to approach in America because people think of them only in American terms and in terms of crime, which I think is very myopic. If you want a gun to do crime in America, it's easy to get one. There are more guns than people in this country. But for someone in Myanmar, it is not the case that it's easy to get a gun. And so for them, this ability to manufacture them changed everything. It gave them a means to defend themselves. It gave them a means to stand up against the government.

It's not just guns; there's other infrastructure going on here. We're talking like the internet. We're talking about something that is highly controlled, often by the state. How are they navigating this? We're now aware of these sorts of movements, and people can hear what's going on. How are they using that technology to their advantage?

I think they make a big effort, like, right, especially with the internet stuff. If you look at young folks in Myanmar, they're so connected, they're so I don't want to use online because I think it has like a derogatory sense. They accept that sometimes, when I was speaking to this young guy with the Gen Z army who I spoke about earlier, the translator would translate it as tech savvy, which, again, kind of doesn't quite draw right in English the way I would like it to. But I think the fact that they're able to navigate the Internet basically by Starlink, which is unfortunate. Like it's, it's very unfortunate that they rely on it and I know that the EU is developing an alternative to Starlink, and that will be good. Starlink is how they get the internet in free Myanmar, because the government has attempted to shut the internet down, and they've attempted to shut the internet down because people were getting out their story. It elicits what I think is a very universal human response: Oh, these are just kids who want a fair chance at life. They want a better future. They want the things that all of us want, and why the hell wouldn't we want them to have them? And when the world can see them, the world supports them, even if only rhetorically. There's a very obvious incentive for the government to shut that down.

But they've had to handle everything. Like there are hospitals in liberated zones for Myanmar, there were schools I know, like some of the people who I've spoken to who are involved in the revolution are also teaching. They also had things that they did in their past lives. They were English teachers, they were artists, they were poets and musicians, and now they're teaching kids to play guitar, like they've had to organize all of that from the ground up, but they've been able to. That wasn't beyond them. If they can take on the government and push it back and liberate territory, then there's nothing they can't do in that territory. In Myanmar, a lot of medical professionals have joined the civil disobedience movement, so they have joined the revolution in that way, albeit they don't, obviously, take up and carry arms, but they do provide medical care to people in the liberated zones. The same is true in Rojava, like you have hospitals, of course, that existed before the Rojava revolution, but they have had to work out ways to keep those going in very creative ways because of the embargo and the difficulty of getting material goods. When I was in Rojava, they were appealing for people to come and donate blood because the toll of the drone strikes was so high that they needed people to come and give blood, and people were queuing outside the hospital to give blood.

They had to navigate all those things like they did in Spain, too, if you look at how they organized in Spain. They collectivized a lot of industry, and then they worked out a way that they could also subsidize collective industries that weren't functioning. For instance, so many people were using the tram in Barcelona that it was making more money than it needed. Everyone was paid a dignified wage, and then all the operations of the tram were taken care of. And so then they were like, Okay, well, it looks like the people in this town need to get from A to B. They need transport, right? But there aren't enough of them for transport to fund what we wanted to, so we'll send some of the money we have left over over there, so they can have that. They were able to develop a pretty advanced economic cooperation that facilitated doing all the other things in addition to conflict, in addition to fighting, in addition to obtaining guns and ammunition. In Spain, the obtaining of guns and ammunition was the hard part for them. The running of the civilian economy was not. They were doing fine in terms of, like, collectivized factories producing the necessities for everyday life, but they did not have a great deal of arms manufacturing and had probably even less ammunition manufacturing, so that was really a bottleneck for them.

I see those as other ways, not just armed struggle, that are daily actions of making the state obsolete. I saw it with the wildfires and obviously the ICE raids, but it's just sort of like, They're not here to save you. We can take care of ourselves. And really, you know, the city and county out here just sort of like, "We'll get the Red Cross" or whatever. But most of the help came from everyday people. That's always the thing about anarchism—well, what are we going to do about the teachers and, you know, the bus driver—all of this, and what it sounds like is that they found ways to answer that question in these conflicts.

What are we going to do about the teachers? The people who are drawn to teach will teach, and like they will, you know, we'll take care of them, and when they need something to eat, we'll give them some food. And what're we going to do about the bus drivers? Well, specifically, what they did in Spain was immediately begin in the transport union being like, Yo, I bet some ladies really fucking love a bus, but you guys have been excluded from this because of misogyny, and so they the transport Union began training up women who would like to be bus drivers. People love fucking bus driving. People love buses and shit trains. Like there's a segment of society for whom those are very interesting.

My YouTube algorithm has a section just about public transit, and I can confirm that people fucking love buses.

People always say, like, "Oh, well, who makes trains run on time?" The fucking train people will. They love that shit!

What in this current moment can people do and learn from these stories in your book? What can we do now to minimize harm and sort of fight back again?

There's so many things that we can do that aren't violent, and we should do them first. And the way to do that, first of all, is to build alliances, like there are going to be people with whom you have disagreements, and like all of these movements are characterized by the fact that they're not, you know, homogenous. They're heterogeneous, right? They have different tendencies within them, but you're all going to be pushing in the same direction. One of the things that I have seen again and again and again and again destroy any movement for positive change in this country is the absence of accountability and the refusal of people to take accountability. One of the things that the Kurdish Freedom Movement has developed is its idea of—you could call it criticism and self-criticism, and that procedure is one I wish we'd had in mutual aid groups I've been with so that we could air things that we felt weren't going well, and we could do that from a position of being like, I care about you, and the reason I'm giving you this criticism is is that want to help you become the person I know you want to be. And then we could have discussed and hopefully continued to wrap all of that in caring about one another and wanting each other to be better, and avoided some things that blew up so many groups, and we can do all of those things right now.

We have not exhausted those options. We are not in the same situation the people of Spain were in when their military rose up. I'm not saying that it's not possible that we will get there. I'm saying that that's not where we're at. And I think sometimes people fetishize violence or struggle as the only form of struggle, and that's extremely toxic, like we need to be struggling just as hard to care for one another, and like that can manifest in so many different ways.

But we're seeing people are out there, like people in Minnesota right now are out there putting their bodies in between the state and vulnerable people. It's incredibly brave. In a sense, it's admirable. And there are—I don't know how many thousands of agents there are in Minnesota right now, but clearly there are a lot. And those ICE agents who are so busy shouting at middle-aged moms aren't grabbing people because they're occupied shouting at middle-aged moms. I think we should not just look at the end result of armed conflict, but we should look at the ways that people have organized under stress, and consider armed conflict to be a type of stress, but we are in a situation which is also very serious and very stressful, and we can learn to organize from them, and we can take those skills and use them in a time when armed conflict is not something that's happening like it is their country.

We're very long way from this country's capacity for state violence, and we don't want to go further down that road if we can avoid it at all. We do not want the full violent capacity of the United States released on its citizens. That's a petrifying thought. And if there's one thing I've learned writing about war and studying conflict, it's that it's horrible. It's something that none of us should want. All of us should try to avoid it at all costs. I'm not saying that my friends in Myanmar or Syria should've avoided conflict. They didn't have an option, and I'm proud of them for being brave.

The way I took what you were writing about in this book to some degree is to look at what's possible. That this idea of, like, statelessness is a possibility. Like this isn't just a utopia, you know?

It's real. And you can get on a plane and go, and if you're interested in, you want to see it, you should. That's something else I would really like people to take from this is that in the darkest times, people can build the most beautiful things. And that is something that I have experienced personally. I have this really special memory of being in Kurdistan, and it's nighttime, and there's drone bombings happening in the area that I'm in, so I'm not going out. I'm inside with some people I've just met. They have bought a songbook and they're playing music, they're singing, and they're telling stories. I want people to understand that even in a place that has been at war for a decade, where they've had to fight and people have had to die for every scrap of land and for every freedom they have, that people have built beautiful things. There are little children having fun running around the market every day.

The same is true in Myanmar. You'll see videos of the Karenni folks, and they're very famous for this, they will get together in their formation and have a music concert, or, like, have a dance party. I want people to see that not only is it possible, it's not that far away, and that we don't have to be like, monastic about it. Won't have to be like, I know sometimes there's this idea that, like everything has to be so fucking serious. And I understand we're in very serious times right now, but people can build beautiful things and they can have joy.

Even in these really dark times, we can and should remember beautiful things, that people can build beautiful things, and that we should have hope. I think in this country right now people could stand to be more hopeful. I know I missed you when I was in LA. We were there on different days, and things were pretty bad there. But like, I also derive hope from the fact that after three or four or five days of state violence, people still continued to show up. People continue to take care of each other. You know, I saw people being tear gassed and helping a stranger right or being shot at with whatever they are, 40-millimeter foam rounds, and then taking the time to help someone who's fallen down or whatever. I saw people just show up with sandwiches and bottles of water and shit, and we should remember that.

It's a dark time for this country right now, but a lot of people have been through dark times, and beautiful things can happen even despite those dark times.

I don't want people to lose hope. And I hope that this book, like obviously, the Spanish revolution did not succeed, and the revolution in Myanmar and a revolution in Rojava are still ongoing, but even during their struggles, there have been so many victories and so many little moments of beauty that I hope people can understand that and hope for that for themselves.

You and I have seen massive state violence up and down the west coast here. But I always think about how at no point did I ever attend a march or whatever I was covering in 2020/21 and wonder if I was going to need enough snacks, because there was always someone to give me snacks, and there was always someone to bring water.

I hope people are creating that in the streets in Minnesota right now. Like we should celebrate that, and then we should think, how can we scale that? How can we make that bigger? What can we do to take care of each other when the people we thought were supposed to help us aren't helping us? Like, I don't see Tim Walz in the street in Minnesota. You know, I didn't see Gavin Newsom when I was in LA, but I saw a whole bunch of people who didn't really need Gavin Newsom because they were taking care of each other.

That's the way it should be. We shouldn't have to do that, but also good that we do and that we can.

Yeah, no. Like he can fuck off, like he's, like he's made his choices, right? Like there are many tools that are available to him that he has chosen not to use, and that's fine. He's made a choice, and other people have made a choice, and those choices are going to lead them in different directions, and that's okay. But we should remember that we don't have to feel hopeless because we don't have these institutions behind us, because, like, all those institutions are made up of people, and if we have people behind us, we'll be okay.